MISTEL DOBERMANS

TEN GENERATIONS OF

BREEDER OWNER HANDLED CHAMPIONS

The following is an article describing Doberman

movement or gait

written by Bob Vandiver and

published in the Doberman Digest

The Doberman was originally bred for protection and

accompaniment during Herr Doberman’s rounds as tax

collector.

Through the history, the Doberman has been

used for many tasks including delivering messages

during war, patrolling military objectives, police

work, search and rescue, guide dogs for disabled,

and in ring sports including conformation,

obedience, agility, tracking, and schutzhund. These

varied tasks require that the Doberman use many

gaits, depending on the task at hand.

Some breeds have natural gaits that are specific to

them.

Examples include the hackney gait of the Minpin, the

flying trot of the German Shepherd, or the amble of

the Old English Sheepdog.

These gaits are characteristic of the breed.

The Doberman has been said to be a galloping breed,

and it is most comfortable at that gait.

However, upon observation of many Dobermans

in a natural environment, you will find that the

breed is comfortable in several gaits, including the

walk, trot, canter, and double suspended gallop.

The breed uses any and all of these gaits

depending on the need.

For practical purposes, the Doberman is evaluated at

the trot in the show ring (as are most other

breeds).

For this reason, this discussion will be

limited to that gait.

Overview

The most efficient working dogs are those that can

work the longest at their appointed duties with the

least amount of effort.

The efficiently moving dog travels in a

straight line with the minimum amount of energy.

It requires that there be no bouncing,

rolling, or yaw (twisting on the vertical axis).

Length of stride of the dog is an important

consideration.

For a given dog, the fewer steps required to

cover a given distance, the less energy is required.

In most dogs, the rear provides the major propulsive

force for moving.

The back and loin provide the rigidity to

transmit the force from the rear to the front.

The front carries about 60% of the weight and

provides some additional propulsion.

The Doberman Standard describes the gait as “Free,

balanced and vigorous with good reach in the

forequarters and good driving power in the

hindquarters.

When trotting, there is strong rear action

drive.

Each rear leg moves in line with the foreleg on the

same side.

Rear and front legs are thrown neither in nor

out. Back remains strong and firm.

When moving at the fast trot, a properly

built dog will single track.”

Evaluating the side gait

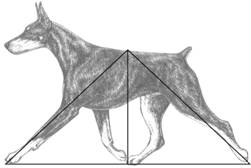

Pictured below is a side view of the Doberman at a

trot.

The graphic was taken from The Doberman Pinscher

Illustrated1 issued in 2006 a booklet

prepared by the Doberman Pinscher Club of America

(DPCA).

We will begin the discussion with the first

line of the movement description “Free, balanced and

vigorous with good reach in the forequarters and

good driving power in the hindquarters.” Note the

front reach and the rear extension in Figure 1 below

Figure 1

Using the same graphic we can draw a triangle over

the dog as seen in Figure 2 below to visualize

proper leg position.

Figure 2

The front reach of the dog should result in a front

extension approximately below the nose.

The rear extension should balance the front

with an equal kickback.

As you can see, the triangle’s apex is just

above the point at which the front foot and rear

foot exchange positions (about the center of the

dog’s topline).

The angle that forms the front reach is about

equal to the angle that forms the rear extension.

This is balanced movement and illustrates

correct Doberman side gait.

When evaluating gait, it is important to consider

the elevation of the feet.

If a dog lifts front or rear feet excessively

above the ground, he is wasting energy.

The closer the feet remain to the ground, the

less energy is required.

There is an old dog term called “daisy

cutting” that describes an efficiently moving dog as

one whose feet are raised just enough to cover the

rough ground, just cutting the tops of the daisies

as he moves.

To study the side gait, follow the footsteps as the

dog moves.

At the trot, the dog is continuously moving

over the legs.

The front foot strikes the ground slightly

behind the nose and immediately moves rearward.

As it moves it passes under the front

assembly to the point at which it lifts from the

ground to move forward again.

The leg in the rear on the opposite side is

simultaneously following the reverse path.

It is leaving its extended position and

moving forward under the rear assembly, and

extending to about the midpoint of the dog’s body.

Just under the center of the topline, the

front foot lifts to move forward for the next step.

The rear foot steps into nearly the same

track that the front foot vacates.

There is a very slight forward motion of the

entire dog’s body when both front and rear feet are

off the ground simultaneously. This allows the rear

foot to assume the same position as the vacating

front foot.

(Otherwise the rear foot would interfere with

the front foot.)

This slight forward motion is what Rachel

Page Elliot2 describes as the “spring” in

the gait.

It contributes to the look of “free and

balanced” motion as described in the standard. Some

characterize it as gliding or floating.

This slight time “in flight” is not visible

to the naked eye, but it has been demonstrated in

Elliot’s scientific studies2 and it can

be seen in the smoothness of the gait.

Since the rear provides for most of the propelling

motion, it is important to note its action.

The rear leg motion can be thought of as a

3-phase action.

In the first phase the leg reaches under the

dog to strike the ground at about the same point

that the front foot is vacating.

The upper leg and hip muscles are doing most

of the work.

In the second phase, the leg swings backward

under the dog’s hip assembly and uses mostly the

upper leg assembly for its power. In the third

phase, the rear leg continues from under the hip

assembly rearward.

A combination of the upper leg and the

extension of the rear pastern provide the propelling

force.

Near the end of this phase, the rear pastern kicks

back to provide most of the final propulsion.

The end of the last phase tells us why the rear

pastern (a seemingly small part of the leg) is so

important in the overall movement of the dog.

Comparing a dog’s anatomy to a human’s is

hardly exact, but the human’s upper and lower thigh

is analogous to the dog’s upper and lower thigh.

The ankle is analogous to the dog’s hock, and

the human foot is used similarly to the dog’s rear

pastern.

Toward the end of the step, the human pushes

off with the foot. The same is true for the dog with

the rear pastern.

You can imagine how you would move if your

feet were confined by tape such that you could not

flex your foot.

You couldn’t provide that final push for your

forward propulsion.

The same is true of the dog.

This illustrates the importance of the rear

pastern power at a trot

…

human or canine.

The standard states “Back remains strong and firm.”

This simply requires that the dog’s back be

reasonably rigid and strong, and not bounce due to

looseness, length, or incorrect proportions or

angulation.The topline of the Doberman should remain

level and straight. A Doberman that bounces

over the withers has a serious handicap.

Let’s try to quantify the affects of a

bouncing front due to a combination of structural

deviations.

If a male Doberman has a stride of 28 inches at the

trot (2263 steps per mile), and the withers move up

and down 1/2 inch with each step, then the dog’s

front will expend the energy equivalent of lifting

it 94 feet while traveling that mile.

Since the dog’s front is about 60 % of the

dog’s total weight, then the dog would have expended

60 % of the energy to raise his entire body the 94

feet.

In other words, after trotting for a mile, the dog

will have also expended the energy equivalent to

climbing a 6-story building (60% of the 94 feet).

The extra work expended in an hour of trotting

(typically at 5 miles per hour) would be the

equivalent of climbing 30 stories.

After a days work, this dog will be far more

exhausted than one that moves without bounce over

the withers.

Moving on with side gait, the head carriage should

be extended somewhat above the horizontal as shown

in figure 1.

This is a natural head carriage for the

Doberman at the trot. The Doberman should not move

with its head extended straight ahead as if it were

a draft animal or with the head up and back as is

typical in a Poodle.

Evaluating the down-and-back gait

The down-and-back gait is described in the standard

as “Each rear leg moves in line with the foreleg on

the same side.

Rear and front legs are thrown neither in nor

out. …

When moving at the fast trot, a properly built dog

will single track.” Figure 3 below shows the

correct movement down and back for a Doberman.

Figure 4 has lines added to emphasize that

the leg forms a straight-line column and moves in

the same plane as the opposite leg on the same side

and converge toward a centerline under the dog.

Figure 32

Figure 4

The importance of moving with straight legs can be

appreciated if we compare the dog’s legs with human

legs.

It is truly a rare human endurance athlete that does

not have very straight legs.

Knock-knees or bowed legs do not allow the

forces to travel directly though the joints.

Rather, they cause a lateral force in the

joints that will damage the joints over a period of

time, and cause the athlete to move inefficiently.

The same reasoning applies to dogs that do

not maintain straight legs throughout the travel.

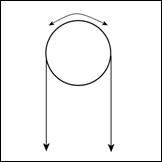

The standard calls for the dog to single track at a

fast trot.

The purpose of the single track is for

balance and conservation of energy.

Consider a dog that doesn’t single track at

the trot.

Such a dog would have a tendency to have a

body roll.

This can be illustrated by Figure 5 below:

Figure 5

Although some Dobermans fail to converge properly,

they do not have an exaggerated rolling or twisting

of the body that is seen on the wide set dogs.

However, the tendency is still there for the

dog to move similarly to the Bulldog.

It is not an efficient gait for a working

dog.

When judging the Doberman, convergence is an

important point.

The dog must also move in a straight line with a

straight body to be an efficient mover.

Some structural faults will cause a dog to

move with a yaw or in a “side-winding” or “crabbing”

gait.

This takes away from our desire to have the dog move

in a straight line, with minimum bounce, roll, or

yaw.

Although the dog will appear to move in a straight

line, it will not move with its body (spine) in line

with the direction of motion.

How structure affects movement

At a show, the judge does a static evaluation to

consider head, color, coat, condition, temperament,

structure, etc..

The structural considerations in this

evaluation can often predict how a dog will move,

but there are reasons why the conclusions reached

from the static structural evaluation do not match

how the dog really moves.

The structure and the musculature of the dog control

the movement of the dog.

If the dog is in proper physical condition

(weight, muscle tone, and ligament and tendon

strength), then its musculature is not a

consideration.

The dog will then move as well as the

structure will allow.

However,

lack of proper musculature and conditioning can make

an otherwise correctly structured dog move poorly.

This is particularly noticeable in front

movement. The shoulders are not connected to the

rest of the structure through joints, but rather

they are connected through soft tissue (muscles,

tendons, etc.).

It is entirely possible for a dog to move

incorrectly through lack of conditioning rather than

through fault of structure.

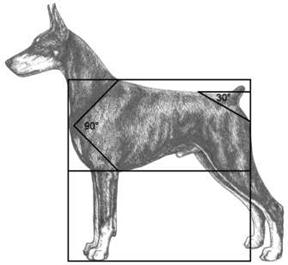

Most judges agree that observing the movement of the

dog is ultimately the best way to determine if the

static evaluation is correct. To move

correctly the dog must be structured correctly.

The correct Doberman structure taken from

The Doberman Pinscher Illustrated1 is

illustrated in Figure 6 below:

Figure 6

This structure exhibits the proportions and angles

that define a correct Doberman Pinscher. Deviations

from this structure will cause deviations from the

ideal movement.

The following highlights how certain structural

deviations affect movement of the Doberman.

The first structural issue is the very important

requisite that the Doberman be square.

Two variations can occur.

The dog is too long in body, or the dog is

too short in body.

Unlike breeds whose bodies are longer than

tall, a square dog must really be built to

the correct proportions and angles if it is to move

correctly.

There is simply no extra room to accommodate

any interference between front and rear legs on a

square dog.

Consider a square dog with an over-angulated rear

relative to the front.

The excess rear angulation causes an

over-reach in the rear so that his rear feet

interfere with the front feet.

A square dog must find a way to compensate

for the imbalance so that his legs do not interfere

under his body.

He can compensate by moving with his rear

feet to one side of the front feet, or he can move

wide in the rear so his rear feet don’t strike the

front feet.

A longer bodied dog offers more room under his body,

so his feet will not interfere. The extra room

forgives faults that would be readily apparent in a

square dog.

The longer bodied unbalanced dog may appear

to move correctly, but he has two faults, imbalance

from front to rear and too long in body.

A Doberman with leg length longer than body

depth will have the same problem with interference

under the body.

There will not be enough room under the dog

to place his feet without interference, because the

long legs “overstep” what his body length can

accommodate.

His back feet strike the front feet before

the front foot can get out of the way.

His compensation is similar to the dog that

is overangulated in rear relative to front.

Typical movement for both of these deviations in

structure is a dog that “side-winds” or “crabs” when

he moves.

He moves with his rear to one side of his

front, so that his rear feet strike the ground to

one side of his front feet.

This gives him the appearance of moving

sideways or moving like a crab.

Another means to compensate for this structural

deviation is the dog that moves wider in the rear

than in the front.

This occurs in Dobermans occasionally, but

the breed is much more likely to side-wind than to

move wide in rear.

Continuing with the subject of front structural

deviations, consider shoulder angulation.

The standard calls for the shoulder to be at

45 degrees from the vertical.

There is an old adage that says that a dog

“can’t reach past his shoulders”.

This means that when the dog extends his leg

for the step forward, the angle of the leg will be

controlled by the angle of the shoulder.

A dog with a steeper shoulder than in Figure 6, say

35 degrees from the vertical rather than 45 degrees,

cannot reach as far forward.

One result is a dog that takes shorter steps

both front and rear. Think about a person whose

normal stride is shortened by 10%.

That person suddenly has to take 10% more

steps to cover the same distance … an uncomfortable

gait.

The same applies to the dog.

For a given dog, the longer the natural

stride, the more efficient the gait.

Although the front and rear move at the same speed

with the same number of steps, it’s possible that

the stride lengths are not equal.

This can happen if the dog is unbalanced with

more rear angulation than front angulation (a common

occurrence in Dobermans).

In this case his front stride is shorter than

his rear stride.

To compensate, he must lift his front higher

than normal to keep it in the air longer, while his

rear takes longer strides.

The front is taking shorter strides, but is

airborne for a short time.

This structure causes the dog’s front to

bounce up and down and is a very inefficient gait as

was quantified earlier.

The correct Doberman front as viewed from the

front is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7

Figure 8

In addition, the pinched-front deviation will cause

the dog to throw the front legs from side-to-side,

wasting even more energy. The dog that elbows out

will typically throw the front legs outwards as he

moves … another inefficient gait.

Before leaving the front, it is important to

consider the feet and pasterns.

The standard describes them as “Pasterns firm

and almost perpendicular to the ground. Dewclaws may

be removed. Feet well arched, compact, and catlike,

turning neither in nor out.”

Figure 9

Figure 10

Having completed the front structural deviations,

now consider the rear.

Rear movement is easier to judge than front

movement because the legs are joined to the rest of

the structure through joints, not through soft

tissue alone.

Rear movement is more influenced by

structure, and not as greatly influenced by

conditioning.

Also the movement of the rear is less complex

than that of the front, because the shoulder moves

up and down and rotates through its normal movement.

The rear does not have this complexity.

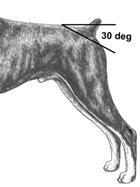

The standard describes the rear as follows:

“The angulation of the hindquarters balances that of

the forequarters.

Hip Bone- falls away from spinal column at an

angle of about 30 degrees, producing a slightly

rounded, well filled-out croup.

Figure 11

Since the Doberman is described in the

standard under General Characteristics as “Compactly

built, muscular and powerful, for great endurance

and speed.” one would expect to see a hock that is

moderate in length to achieve the desired balance of

endurance and speed.

A long rear pastern is normally associated

with sprint type animals such as rabbits or

antelopes … good for short bursts of high speed, but

not endurance.

A short rear pastern is normally associated

with a draft animal … slow but powerful and

enduring, but not capable of great speed.

Since the Doberman is neither of these we

must reach a balance, so a moderate length of

hock-to-foot is desired.

One good way to understand correct rear structure is

to study typical deviations.

Some deviations are shown in Figure 12 and

represent from left to right an overangulated rear,

a straight rear with a flat croup, and an

overangulated rear with sickle hocks and a steep

croup.

.

Figure 12

The middle graphic is straight in rear with a flat

croup.

The expected result is a restricted rear motion.

The dog can’t reach under far enough.

His straight stifle and flat croup won’t

allow the rear to extend (similar to a straight

front not allowing correct reach).

The straight hock joint doesn’t provide

enough power to follow through for the rear pastern

“push-off”

The overangulated rear and sickle hocks are

particularly troubling.

The same problems occur as the overangulated

dog above, but with the sickle hocks the rear

pastern can’t straighten.

A dog with these faults will normally move

with his rear under him, never extending with power.

The steep croup will also limit rear

extension.

A combination of faults that are seen from time to

time in Dobermans is an overangulated rear with a

flat croup.

This dog will appear to move correctly

because the flat croup compensates for the

overangulated rear and allows it to reach back.

It appears to be correct, when in fact there

are two deviations in the dog, rather than none.

The standard also states “Viewed from the rear, the

legs are straight, parallel to each other, and wide

enough apart to fit in with a properly built body.

Dewclaws, if any, are generally removed. Cat feet-

as on front legs, turning neither in nor out.”

Again, the standard and the Illustrated Standard

graphics do an excellent job of describing the

desired structure of the rear when viewed from

behind.

Figure 13

Other typical deviations are shown in Figure 14

below and have the same common problem that we saw

in the front deviations.

These legs are not straight as required even

when standing in the normal position (the left being

cow-hocked and the right being open hocked).

Figure 14

Summary

In the beginning, this article explained the correct

side gait and the correct out-and-back movement for

the Doberman Pinscher. The intent was to instill a

vision of the correct movement of the Doberman in

the reader’s mind. Later, the article describes the

mechanics of gait and discussed how certain

structural traits affect it.

Structural faults were used to describe

incorrect movement.

Using faults helps to understand how the dog

should not move.

Although it is important to understand faults and

how they affect gait, the reader must be careful not

to fall into “fault judging” as the primary means of

evaluating movement. Good judges first recognize

merits, and then evaluate the dog’s movement based

on balancing the virtues against faults. To

emphasize the importance of positive judging, below

you will find a repeat of the illustrations of

correct movement along with a repeat of a

description of correct gait as described in the

standard.

Hopefully the reader will focus on these as

the most important element of this paper.

FINALLY, HERE IS THE CORRECT DOBERMAN MOVEMENT

Home Puppies-for-sale Tips-On-Buying-a Pup About Us Champions Breeding-Practices Raising-Puppies Other-Info

Site designed and maintained by RLVandiver